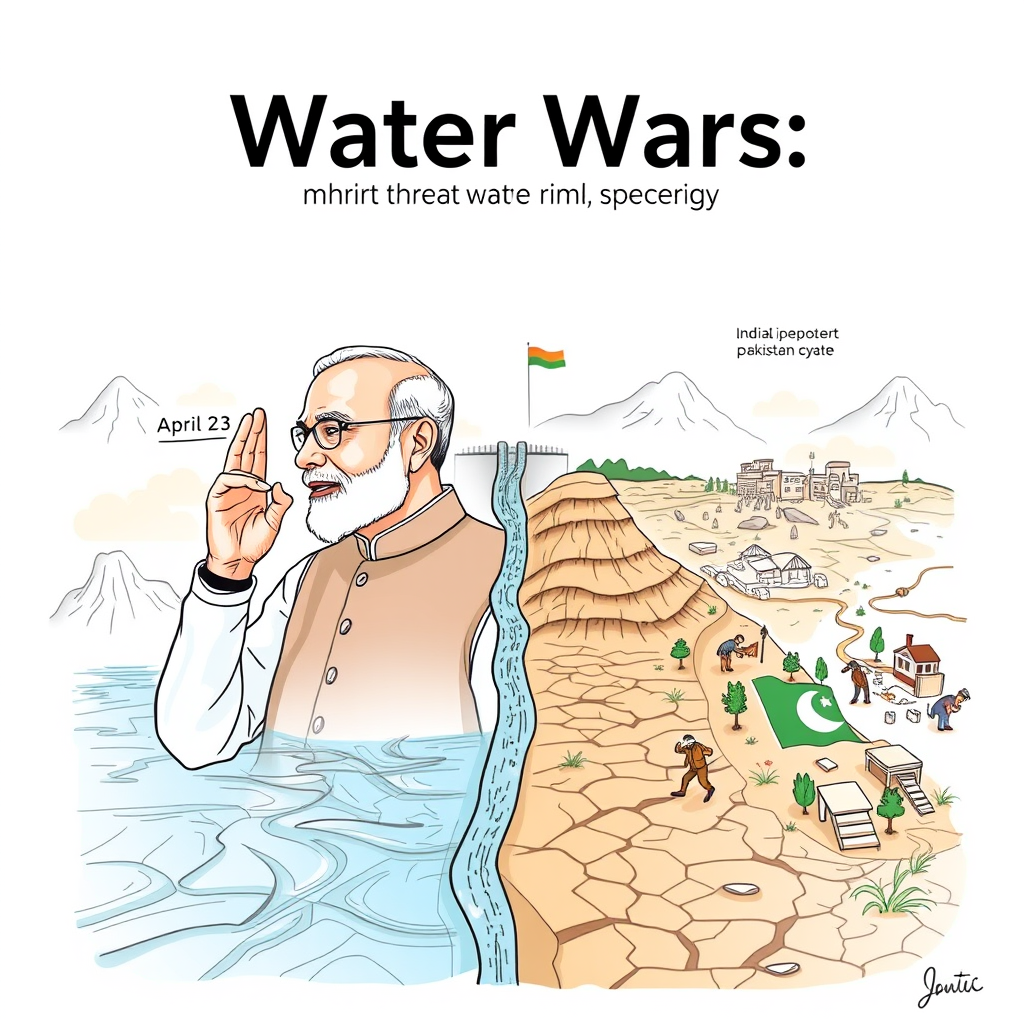

Water Wars: India Threatens Pakistan's Supply

Rewrite the article in a more formal and detailed style:

Title: Escalating Tensions: India’s Threat to Pakistan’s Water Supply

As diplomatic tensions between India and Pakistan persist

- Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi recently announced his intention to cease the flow of water into Pakistan

- stating

- ‘India’s water will be utilized for India’s interests.’ On April 23

- Modi suspended the 1960 treaty that regulates the sharing of Indus Basin waters between the two nations. While the construction of infrastructure to block water flow would take India several years and strain its own resources

- the move could exacerbate Pakistan’s already critical water situation

- which is further compromised by climate change.

Pakistan’s water resources are under severe strain due to rising temperatures

- droughts

- and the melting of glaciers

- which disrupt the timing of water flow. India’s actions could intensify the crisis and pose long-term threats to Pakistan’s agricultural sector. Many Pakistanis already face difficulties in accessing clean and reliable water

- a problem that has been exacerbated by climate change. Following the devastating floods of 2022

- which claimed at least 1,700 lives

- over 10 million people were left without safe drinking water

- according to a UNICEF report.

‘The local populations are already facing significant challenges in accessing consistent water supplies,’ notes Bhargabi Bharadwaj

- a research associate at the Environment and Society Center at Chatham House. ‘Even without the recent escalations in the Indus Water Treaty

- these issues are being felt at the grassroots level.’

The root of the water dispute can be traced back to the 1947 partition of the South Asian subcontinent by the British

- which divided the Indus River between India and Pakistan. ‘The problem began on day one,’ says Hassaan Khan

- an assistant professor of urban and environmental policy at Tufts University. Most of the Indus River’s headwaters are in India

- while the majority of irrigation systems are in Pakistan. Approximately 80% of Pakistan’s agriculture and a third of its hydropower depend on the Indus Basin

- making Pakistan more reliant on this water source than India.

The Indus Waters Treaty

- brokered by the World Bank in 1960

- aimed to equitably divide the river system’s water and included dispute resolution mechanisms. However

- India could still engineer minor disruptions to impact the timing and volume of water flow into Pakistan

- particularly during the low flow season from December to February. ‘India can create disturbances that

- if not managed properly by Pakistan

- can affect the agricultural system,’ says Khan.

Despite these challenges

- the Indus Water Treaty has proven resilient

- enduring two previous wars and another conflict between the countries. ‘The treaty’s strength lies in its design

- which has allowed it to withstand numerous tensions over the years,’ says Bharadwaj.

Pakistan’s water scarcity crisis predates the country’s founding

- with disputes over water for agricultural projects dating back to the 1930s and 1940s. Climate change and rapid population growth have worsened the situation

- making Pakistan one of the most water-stressed countries in the world. Last winter was one of the driest on record

- with the Pakistan Meteorological Department reporting 67% less rainfall than usual. The Germanwatch 2025 Climate Risk Index ranked Pakistan as the most vulnerable country to climate change impacts in 2022 due to the devastating floods.

Farmlands are becoming unusable due to increasing droughts

- driving more people into cities and straining urban water supplies. ‘Cities are increasingly water-stressed because water supply hasn’t kept up with population growth,’ says Khan. Over three-quarters of Pakistan’s renewable water resources come from outside its borders

- primarily from the Indus Basin. Any changes to the country’s water supply will have severe impacts on agriculture and livelihoods for millions

- says Daniel Haines

- an associate professor in the history of risk and disaster at University College London. ‘The water system in Pakistan is already so stressed that any disruption

- even to the timing of water flow

- could have serious consequences.’

In conclusion

- the situation serves as a stark reminder of how geopolitical tensions can exacerbate the impacts of climate change. Both countries must prioritize diplomacy and cooperation to manage shared water resources sustainably. Failure to do so could lead to catastrophic consequences for the environment

- economy

- and the millions of people who depend on the Indus Basin for their livelihoods. The international community should also play a role in supporting these efforts and encouraging both nations to uphold the Indus Waters Treaty

- which has proven to be a crucial mechanism for managing transboundary water disputes.

categories:

- Environment

As tensions between India and Pakistan continue to escalate, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi recently pledged to halt water flow into Pakistan, declaring, ‘India’s water will be used for India’s interests.’ On April 23, Modi suspended a 1960 treaty that governs the sharing of Indus Basin waters between the two nations. While constructing infrastructure to block water flow would take India years and strain its own resources, the move could significantly worsen Pakistan’s already dire water situation, exacerbated by climate change.

Pakistan’s water resources are under severe pressure due to rising temperatures, droughts, and melting glaciers, which disrupt the timing of water flow. India’s actions could deepen the crisis and pose long-term threats to Pakistan’s agricultural sector. Many Pakistanis already struggle to access clean and reliable water, a problem compounded by climate change. Following the devastating 2022 floods that claimed at least 1,700 lives, over 10 million people were left without safe drinking water, according to a UNICEF report.

‘The local populations are already facing significant challenges in accessing consistent water supplies,’ says Bhargabi Bharadwaj, a research associate at the Environment and Society Center at Chatham House. ‘Even without the recent escalations in the Indus Water Treaty, these issues are being felt at the grassroots level.’

The root of the water dispute lies in the 1947 partition of the South Asian subcontinent by the British, which divided the Indus River between India and Pakistan. ‘The problem began on day one,’ says Hassaan Khan, an assistant professor of urban and environmental policy at Tufts University. Most of the Indus River’s headwaters are in India, while the majority of irrigation systems are in Pakistan. Around 80% of Pakistan’s agriculture and a third of its hydropower depend on the Indus Basin, making Pakistan more reliant on this water source than India.

The Indus Waters Treaty, brokered by the World Bank in 1960, aimed to equally divide the river system’s water and included dispute resolution mechanisms. However, India could still engineer small disruptions to impact the timing and volume of water flow into Pakistan, particularly during the low flow season from December to February. ‘India can create disturbances that, if not managed properly by Pakistan, can affect the agricultural system,’ says Khan.

Despite these challenges, the Indus Water Treaty has proven resilient, enduring two previous wars and another conflict between the countries. ‘The treaty’s strength lies in its design, which has allowed it to withstand numerous tensions over the years,’ says Bharadwaj.

Pakistan’s water scarcity crisis predates the country’s founding, with disputes over water for agricultural projects dating back to the 1930s and 1940s. Climate change and rapid population growth have worsened the situation, making Pakistan one of the most water-stressed countries in the world. Last winter was one of the driest on record, with the Pakistan Meteorological Department reporting 67% less rainfall than usual. The Germanwatch 2025 Climate Risk Index ranked Pakistan as the most vulnerable country to climate change impacts in 2022 due to the devastating floods.

Farmlands are becoming unusable due to increasing droughts, driving more people into cities and straining urban water supplies. ‘Cities are increasingly water-stressed because water supply hasn’t kept up with population growth,’ says Khan. Over three-quarters of Pakistan’s renewable water resources come from outside its borders, primarily from the Indus Basin. Any changes to the country’s water supply will have severe impacts on agriculture and livelihoods for millions, says Daniel Haines, an associate professor in the history of risk and disaster at University College London. ‘The water system in Pakistan is already so stressed that any disruption, even to the timing of water flow, could have serious consequences.’

In my opinion, the situation is a stark reminder of how geopolitical tensions can exacerbate the impacts of climate change. Both countries must prioritize diplomacy and cooperation to manage shared water resources sustainably. Failure to do so could lead to catastrophic consequences for the environment, economy, and the millions of people who depend on the Indus Basin for their livelihoods. The international community should also play a role in supporting these efforts and encouraging both nations to uphold the Indus Waters Treaty, which has proven to be a crucial mechanism for managing transboundary water disputes.