RFK Jr.'s Health Advice Sparks Outrage From Doctors

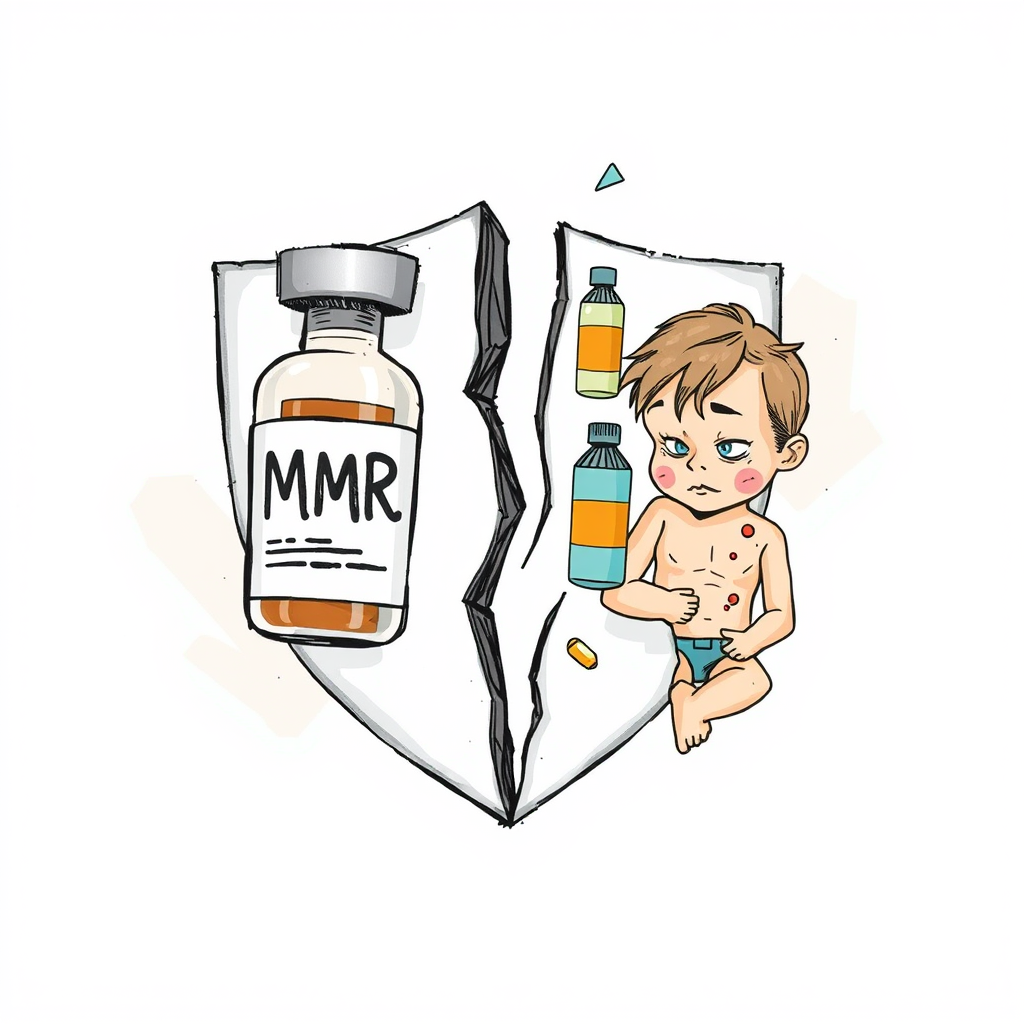

Health experts are voicing serious concerns over a directive from Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. to prioritize research into alternative measles treatments – including vitamins – over the promotion of established vaccinations. The move, reported by The New York Times, is being widely criticized as a dangerous departure from proven public health strategies.

Dr. Jonathan Temte, former chairman of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s vaccine advisory committee, likened Kennedy Jr.’s approach to neglecting preventative care in favor of treating advanced illness. “This is akin to saying, ‘Go ahead and eat whatever you want, don’t exercise, smoke like a chimney – we’re going to invest all of our resources in heart transplants,’” he told the Times.

The decision arrives amidst a significant resurgence of measles, with the nation experiencing its largest outbreak in 25 years. As of Friday, the CDC reported over 930 cases nationwide, largely concentrated in the Southwest, where the virus tragically claimed the lives of two young girls.

Experts fear this directive will erode public trust in vaccines, a cornerstone of preventative medicine. The Times’ Teddy Rosenbluth notes the decision appears to contradict Kennedy Jr.’s previously stated focus on disease prevention. Current measles treatment primarily focuses on supportive care – managing symptoms like fever with medications such as Tylenol, and providing supplemental oxygen and fluids – while the virus runs its course.

Jennifer Nuzzo, an epidemiologist at the Brown University School of Public Health, expressed concern that the directive sends the wrong message. “We don’t want to send the signal that you don’t have to get vaccinated because there’s just a way to get rid of it,” she told the Times.

While HHS spokesman Andrew Nixon stated the search for new treatments is intended to aid those who choose not to vaccinate, he affirmed the CDC continues to recommend the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine as the most effective preventative measure.

This situation is deeply troubling. Prioritizing research into alternative treatments in addition to robust vaccination promotion would be a reasonable approach. However, framing the search for new treatments as a potential alternative to vaccination is a dangerous gamble with public health, particularly given the current outbreak and the proven efficacy and safety of the MMR vaccine. It appears to cater to anti-vaccine sentiment rather than addressing the root cause of the problem: vaccine hesitancy and misinformation. The focus should remain firmly on bolstering vaccination rates and reinforcing public confidence in established medical science.