Pakistan's Water Crisis: India's Threat Intensifies

Rewrite the original content using more formal and sophisticated language

- while keeping the same core information. Do not change the meaning of the content. Ensure that no non-English language characters (e.g.

- Chinese) appear in your output.

India’s increasing military tensions with Pakistan have cast a pall over the region

- with Prime Minister Narendra Modi recently announcing that India would cease the flow of water across the border into Pakistan. This declaration was accompanied by the suspension of the 1960 Indus Waters Treaty

- which governs the sharing of water from the Indus Basin between the two nations. While constructing the necessary infrastructure to halt the water flow would take India several years and further deplete Pakistan’s already scarce water resources

- the move highlights the potential for a deepening crisis.

Pakistan’s water resources are already under extreme duress due to climate change

- which has brought about rising temperatures

- prolonged droughts

- melting glaciers

- and catastrophic floods that disrupt the natural timing of water flow. India’s actions could further aggravate this crisis

- posing long-term challenges for Pakistan’s agricultural sector. Many Pakistanis already face difficulties in accessing clean and reliable water sources

- a situation that has been exacerbated by climate change. Following the 2022 floods

- which resulted in at least 1,700 fatalities

- more than 10 million people were left without access to safe drinking water

- according to a UNICEF report.

‘Local communities are experiencing significant challenges in obtaining consistent water supplies,’ states Bhargabi Bharadwaj

- a research associate at the Environment and Society Center at Chatham House. ‘This issue is already being felt at the grassroots level

- even before the recent escalation over the Indus Water Treaty.’

The origins of India’s control over Pakistan’s water supply can be traced back to the partition of the South Asian subcontinent by the British in 1947. The Indus River was divided along the new borders

- with most of the headwaters located in India and the majority of irrigation systems in Pakistan. ‘Approximately 80% of Pakistan’s agriculture and a third of its hydropower depend on the water from the Indus Basin region,’ Bharadwaj explains. ‘Pakistan is more reliant on this basin than India.’

The Indus Waters Treaty

- brokered by the World Bank in 1960

- aimed to equitably divide the river system’s water and included mechanisms for dispute resolution. However

- India’s recent actions could disrupt this delicate balance. While India lacks the infrastructure to completely sever Pakistan’s water supply

- it could engineer minor disruptions that impact the timing and volume of water flow

- particularly during the low flow season from December to February. These disruptions could have significant repercussions for Pakistan’s agricultural system.

Experts note that the Indus Water Treaty has endured previous conflicts between the two countries

- thanks to its robust design. ‘This is not the first instance of such tensions arising,’ Bharadwaj says. ‘The treaty’s strength lies in its ability to withstand various crises.’

Pakistan’s water scarcity crisis predates the country’s founding. The regions now part of Pakistan are fertile alluvial plains with limited rainfall

- leading to an over-ambitious expansion of farmland that outstripped available water resources. Climate change and rapid population growth have since exacerbated the situation

- making Pakistan one of the most water-stressed countries in the world. Last winter was one of the driest on record

- with rainfall 67% below average. The Germanwatch 2025 Climate Risk Index ranked Pakistan as the most vulnerable country to climate change impacts in 2022

- highlighting the severe flooding that put much of the country’s agricultural land at risk.

As droughts render farmlands unusable

- more people are migrating to cities

- straining urban water supplies. ‘Cities are increasingly water-stressed because water supply has not kept pace with population growth,’ says Hassaan Khan

- assistant professor of urban and environmental policy at Tufts University. Over three-quarters of Pakistan’s renewable water resources come from outside its borders

- primarily from the Indus Basin. Any disruption to this supply will have profound impacts on agriculture and livelihoods for millions.

In my opinion

- the situation serves as a stark reminder of how geopolitical tensions can exacerbate environmental crises. The Indus Waters Treaty has been a beacon of stability in an otherwise tumultuous region

- and its preservation is crucial for the well-being of millions of people on both sides of the border. It is imperative that both countries engage in constructive dialogue to resolve their differences and ensure the sustainable management of shared water resources. The stakes are high

- and the consequences of failure could be catastrophic for an already water-stressed region.

categories:

- Environment

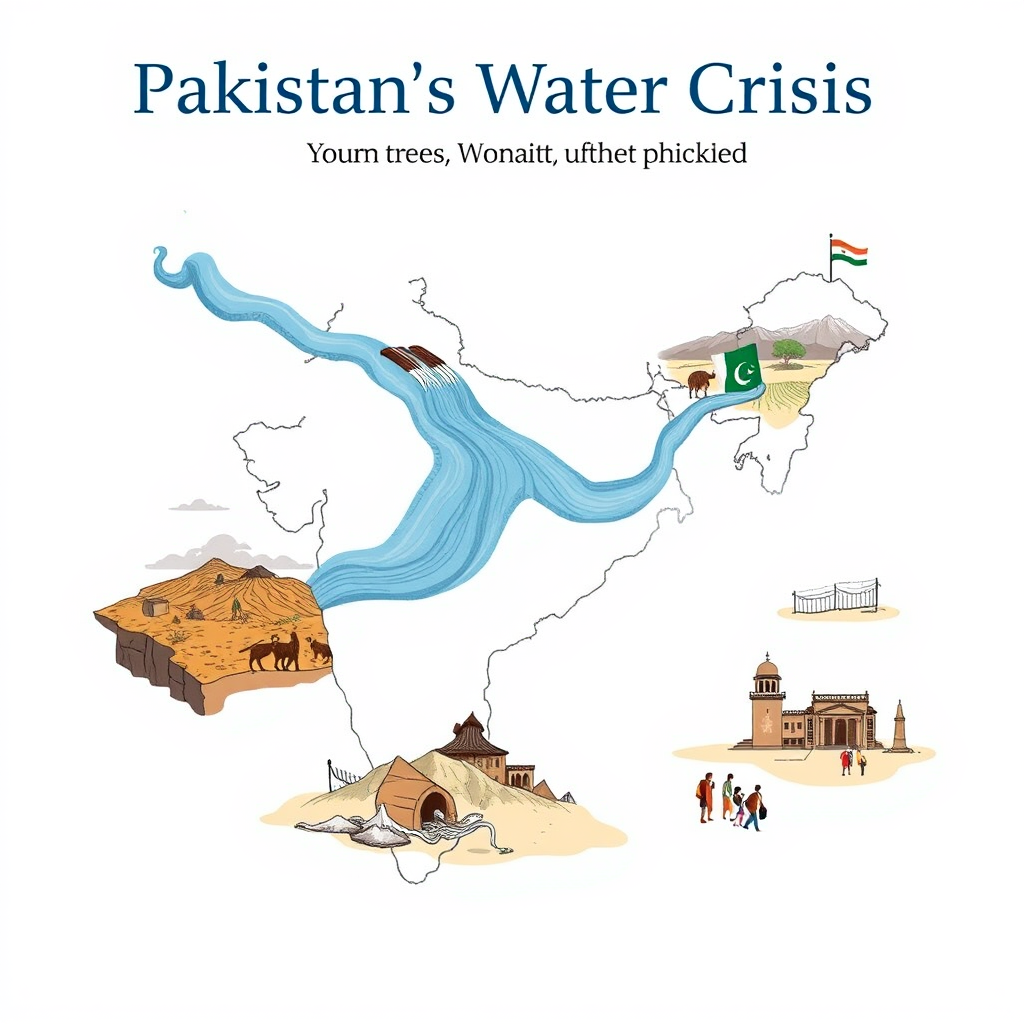

As escalating military tensions between India and Pakistan continue to cast a shadow over the region, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi recently declared that India would halt water flow across the border into Pakistan, stating, ‘India’s water will be used for India’s interests.’ This declaration came with the suspension of the 1960 Indus Waters Treaty, which facilitates the sharing of water from the Indus Basin between the two nations. While constructing infrastructure to block the water flow would take India years and further strain Pakistan’s already limited water resources, the move underscores the potential for a deepening crisis.

Pakistan’s water resources are already under severe stress due to climate change, which has brought rising temperatures, droughts, melting glaciers, and devastating floods that disrupt the natural timing of water flow. Now, India’s actions could exacerbate this crisis, presenting long-term challenges for Pakistan’s agricultural sector. Many Pakistanis already struggle to access clean and reliable water sources, a situation exacerbated by climate change. Following the 2022 floods, which claimed at least 1,700 lives, more than 10 million people were left without safe drinking water, according to a UNICEF report.

‘Local populations are facing significant difficulties in accessing consistent water supplies,’ says Bhargabi Bharadwaj, a research associate at the Environment and Society Center at Chatham House. ‘This issue is already being felt at the grassroots level, even before the recent escalation over the Indus Water Treaty.’

The roots of India’s control over Pakistan’s water supply trace back to the partition of the South Asian subcontinent by the British in 1947. The Indus River was divided along the new borders, with most of the headwaters located in India and the majority of irrigation systems in Pakistan. ‘Around 80% of Pakistan’s agriculture and a third of its hydropower depend on the water from the Indus Basin region,’ Bharadwaj explains. ‘Pakistan is more dependent on this basin than India.’

The Indus Waters Treaty, brokered by the World Bank in 1960, aimed to equitably divide the river system’s water and included mechanisms for dispute resolution. However, India’s recent moves could disrupt this delicate balance. While India lacks the infrastructure to completely cut off Pakistan’s water supply, it could engineer small disruptions that impact the timing and volume of water flow, particularly during the low flow season from December to February. These disruptions could have significant consequences for Pakistan’s agricultural system.

Experts note that the Indus Water Treaty has withstood previous conflicts between the two countries, thanks to its robust design. ‘This isn’t the first time such tensions have arisen,’ Bharadwaj says. ‘The treaty’s strength lies in its ability to endure through various crises.’

Pakistan’s water scarcity crisis predates the country’s founding. The regions now part of Pakistan are fertile alluvial plains with limited rainfall, leading to an over-ambitious expansion of farmland that outstripped available water resources. Climate change and rapid population growth have since exacerbated the situation, making Pakistan one of the most water-stressed countries in the world. Last winter was one of the driest on record, with rainfall 67% below average. The Germanwatch 2025 Climate Risk Index ranked Pakistan as the most vulnerable country to climate change impacts in 2022, highlighting the severe flooding that put much of the country’s agricultural land at risk.

As droughts make farmlands unusable, more people are migrating to cities, straining urban water supplies. ‘Cities are increasingly water-stressed because water supply hasn’t kept pace with population growth,’ says Hassaan Khan, assistant professor of urban and environmental policy at Tufts University. Over three-quarters of Pakistan’s renewable water resources come from outside its borders, primarily from the Indus Basin. Any disruption to this supply will have profound impacts on agriculture and livelihoods for millions.

In my opinion, the situation is a stark reminder of how geopolitical tensions can exacerbate environmental crises. The Indus Waters Treaty has been a beacon of stability in an otherwise tumultuous region, and its preservation is crucial for the well-being of millions of people on both sides of the border. It is imperative that both countries engage in constructive dialogue to resolve their differences and ensure the sustainable management of shared water resources. The stakes are high, and the consequences of failure could be catastrophic for an already water-stressed region.