Iran’s Nuclear Program: Air Strikes Won’t Work

Recent reports of Israeli strikes targeting Iranian nuclear facilities raise a critical question: can military action truly dismantle Iran’s nuclear program? The answer, according to experts and a detailed analysis of Iran’s infrastructure, is a resounding no. While strikes may offer a temporary disruption, they are unlikely to achieve the long-term goal of preventing Iran from acquiring nuclear capabilities.

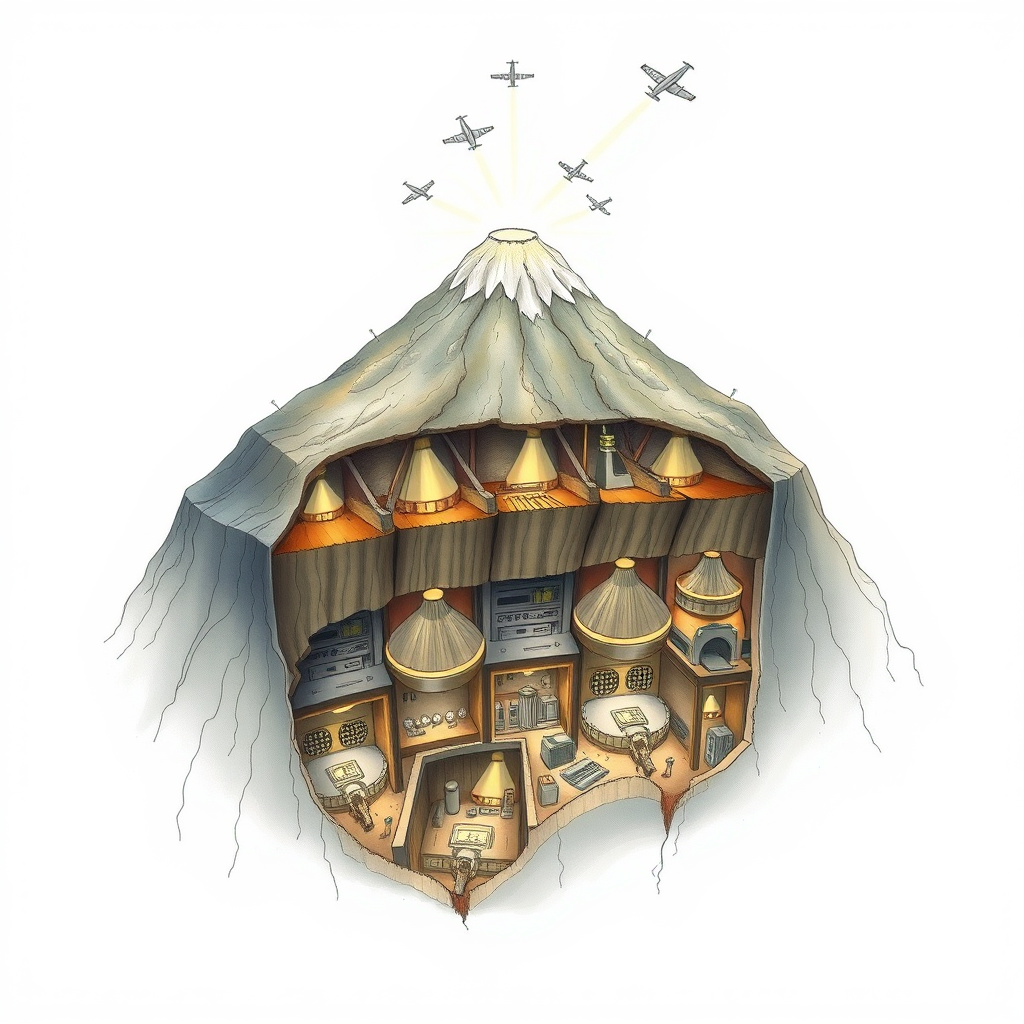

Iran’s program has evolved into a deeply embedded, redundant network designed not just to function, but to survive attack. Facilities like Fordow, buried deep within mountains, and Natanz, with its hardened designs, demonstrate a commitment to resilience. Even if strikes were to damage these sites, Iran’s program extends far beyond them.

Since 2003, Iran has compartmentalized its nuclear work, distributing it across various organizations, including the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran, the Ministry of Defense, and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. This dispersal, coupled with a robust domestic production of key components like centrifuge rotors, renders traditional interdiction strategies ineffective. There are no longer readily targetable foreign supply chains.

The program’s structure mirrors strategies employed by North Korea and, historically, Saddam Hussein’s Iraq – a focus on preserving the capacity to reconstitute, even after significant damage. This is further complicated by Iran’s adherence to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, allowing enrichment activities as long as they aren’t diverted to weapons production – a legal ambiguity Iran skillfully exploits.

Recent intelligence suggests Iran is operating just below the threshold of weaponization, positioning itself for rapid development should conditions change. This posture, formalized under figures like Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, maximizes leverage while minimizing legal risk.

Furthermore, Iran has invested heavily in denial and deception tactics – false facades, underground facilities, and encrypted communications – making accurate battle damage assessment extremely difficult. The lack of IAEA access and continuous surveillance, following Iran’s withdrawal from the JCPOA’s Additional Protocol, exacerbates this problem.

Comparing this situation to past successes – Israel’s 1981 strike on Iraq’s Osirak reactor, or disarmament efforts in Libya and Syria – reveals a crucial difference. Those cases involved pre-operational facilities, limited infrastructure, or were driven by unique political circumstances and full international access. Iran’s program is far more advanced, dispersed, and deeply embedded within its sovereign capabilities.

While airstrikes might buy time, they risk pushing the program further underground, destroying valuable inspection leverage, and potentially triggering the very breakout they aim to prevent. A truly effective dismantlement would require a ground incursion – seizing facilities, securing materials, and either debriefing or removing key personnel – coupled with sustained IAEA and intelligence oversight.

In my view, relying solely on military action is a strategic miscalculation. It offers the illusion of resolution without addressing the core problem: a deeply entrenched program designed to survive and reconstitute. A comprehensive, long-term strategy must prioritize verifiable dismantlement through sustained access, control, and international cooperation, rather than temporary disruption through force. The hard truth is that if complete disarmament is the goal, airstrikes alone will not achieve it.