Inside El Salvador’s Prison Where Demons Beg

El Salvador’s massive new prison, the Terrorism Confinement Center – known as CECOT – didn’t materialize in a vacuum. Understanding its existence requires confronting the brutal reality of gang violence that previously gripped the nation. For over a year, I’ve walked through the aftermath of those killings, spoken with victims, and listened to President Nayib Bukele detail the horrific acts perpetrated by these groups. In May, investigators led me to a chilling example of their cruelty – a “killing field” marked by macabre rituals.

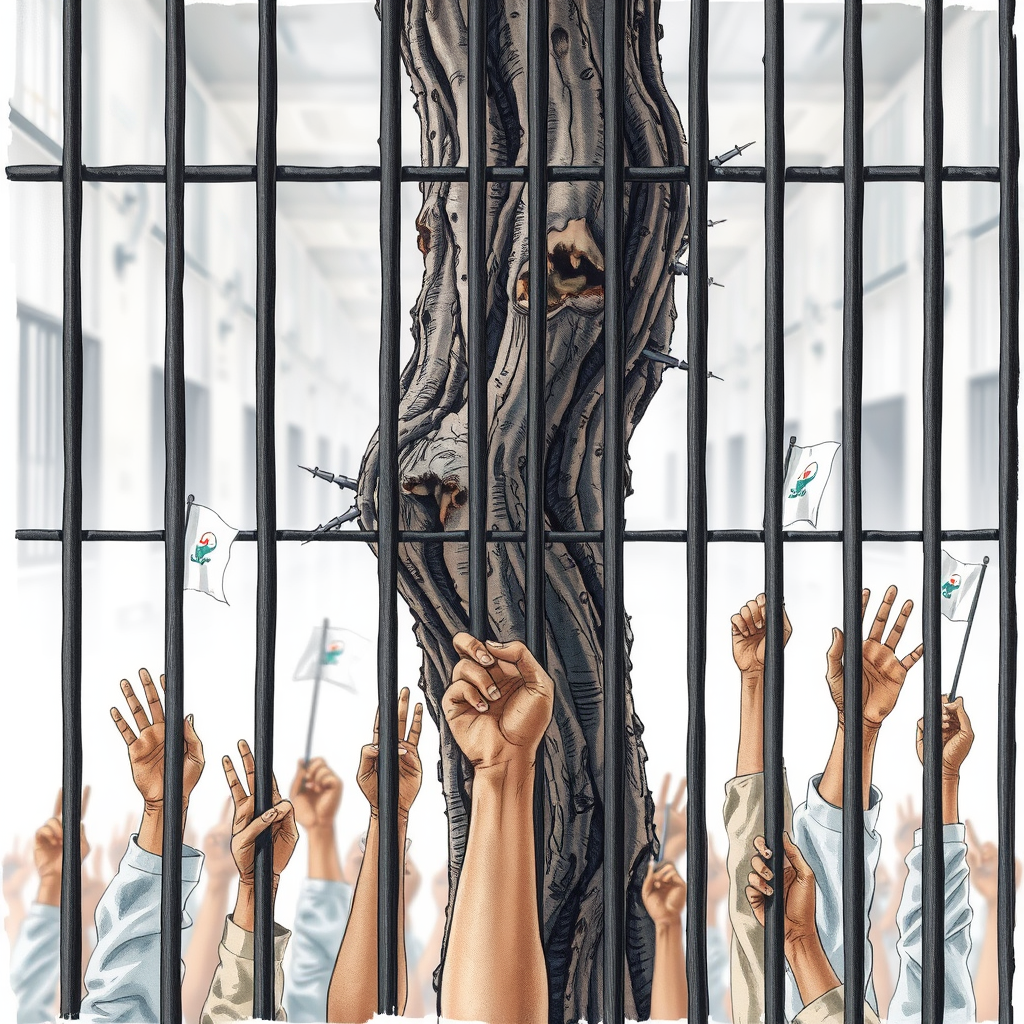

On the slopes of Mount St. Bartolo, an elderly farmer pointed out a scarred tree, its trunk bearing the marks of machetes. “Farmers don’t strike trees,” my guide, Carlos, explained grimly. “That’s where a torso hung.” The ancient Amate tree, leaning precariously over a canyon, held rusty spikes – remnants of a practice where bodies were pinned to the branches in the shape of an inverted cross. The image, and Carlos’s recounting of the horrors, was profoundly disturbing, and remains vividly etched in my memory, resurfacing with every visit to CECOT.

The prison itself is deliberately austere, a stark, almost dehumanizing space. Bukele has stated unequivocally that no prisoner will ever leave alive, and that they will live lives devoid of comfort. However, within CECOT, one module stands in stark contrast: Module 8. It houses the 238 Venezuelan men deported by the United States on March 15th, labeled as members of the Tren de Aragua gang under an emergency order. While Trump Administration officials insisted they were all hardened criminals, subsequent reporting has revealed this to be inaccurate.

I’ve visited Module 8 three times, and each time, the atmosphere has been markedly different from the rest of CECOT. Instead of the eerie silence that pervades the prison, the Venezuelans chant “Liberty!” and “Venezuela!” They vocally proclaim their innocence, their cries echoing beyond the bars. They climb the bars, waving white shirts as makeshift flags, and plead for phones to contact their families. Some shout curses, but no guards intervene. Yet, visitors are also barred from approaching them.

This module is unsettling not because of its cruelty, but because of its relative mercy. Compared to the rest of CECOT, and the broader Salvadoran prison system, the Venezuelans have access to basic comforts: sleep pads, sheets, pillows, and an improved menu that sometimes includes hamburgers. They even have limited access to writing instruments; I saw a scrap of paper with a hastily drawn cross.

I’ve repeatedly asked Salvadoran officials why these foreigners are receiving different treatment. No one has offered a satisfactory explanation. Perhaps it’s a calculated move, acknowledging that these men may eventually be released. Or perhaps, as the title suggests, there’s a subtle acknowledgment that they aren’t viewed as the same “devils” as the rest of the incarcerated population.

During a recent tour of Module 8, I searched for Andry, the “barber” whose image sparked outrage following my initial reporting. We were forbidden from speaking with the inmates, and their uniform crew cuts made identification difficult. Their fearful eyes, however, left a lasting impression. I left with the haunting image of arms reaching through bars, desperate for someone to acknowledge their existence, to believe someone might come.

Reviewing my photographs, I’m struck by the questions they raise. Who are the devils today, and who gets to decide? El Salvador has answered by constructing a massive concrete and steel structure on the side of a volcano, a warehouse for those they deem evil. The U.S. responded by chartering planes to “exorcise” its perceived foreign demons. Within CECOT, there’s austere silence on one side, and chaotic pleas on the other. I think of the rusting nails on that tree, a silent testament to past horrors. They tell a story, but I’m not convinced it’s the story of Module 8. The situation is deeply complex, raising uncomfortable questions about justice, due process, and the very definition of criminality. It’s a stark reminder that even in the pursuit of security, humanity cannot be sacrificed.