India's Monasteries Get New Curriculum, Eyes China

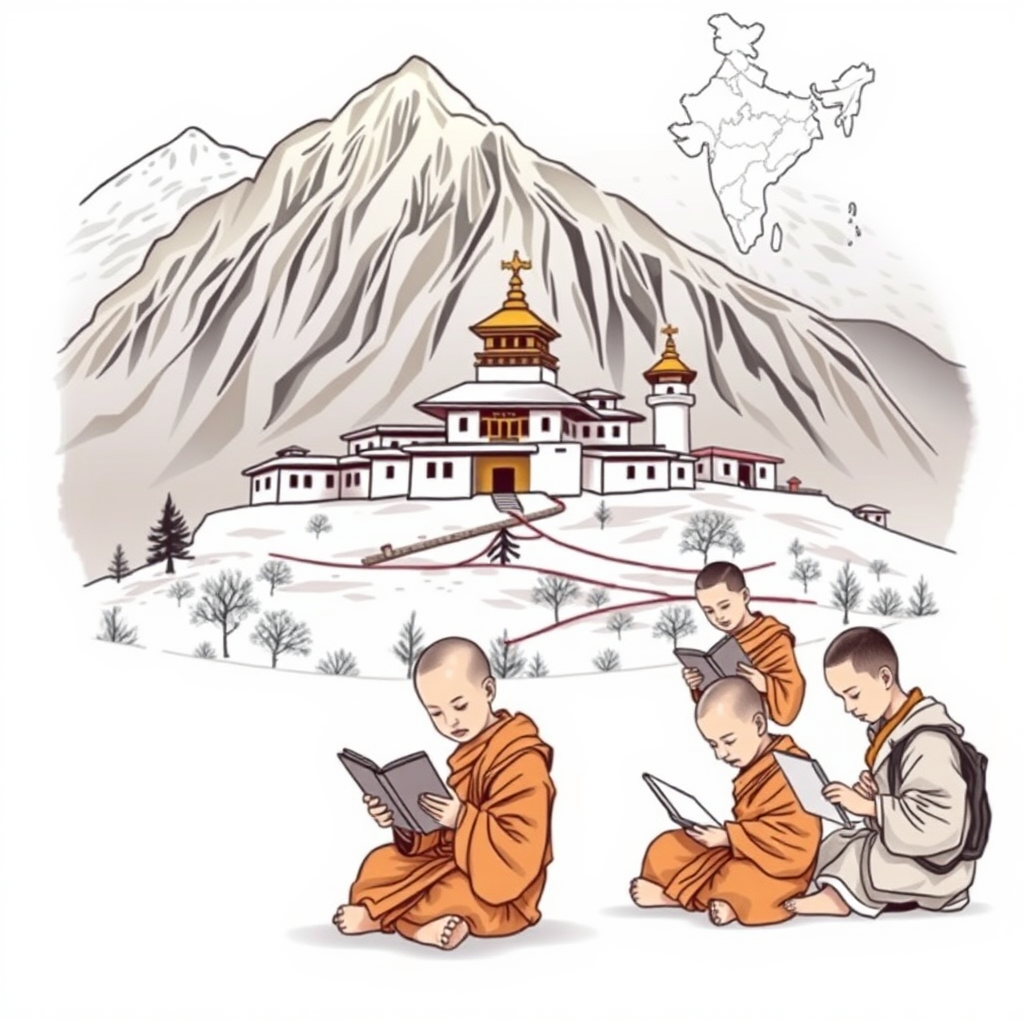

India is implementing a standardized national curriculum for Buddhist monasteries, particularly those located in strategically sensitive Himalayan regions bordering China, in a move officials say aims to strengthen Indian identity and ensure educational opportunities for students while also subtly countering Beijing’s influence. The initiative, rolling out this month, seeks to unify the disparate educational standards currently in place across approximately 600 monasteries scattered throughout northern India – Sikkim, Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Jammu and Kashmir, and Ladakh.

For decades, these monasteries have served as vital centers of learning and refuge, especially following the 1959 Tibetan uprising and the subsequent influx of refugees, including the Dalai Lama. While monasteries have traditionally provided education – encompassing Buddhist philosophy, modern subjects, and English – the lack of formal recognition and standardization has left students with qualifications not readily transferable to the broader Indian education system.

The new curriculum, developed over five years by the Ministry of Education’s National Institute of Open Schooling, will address this gap. It incorporates Indian history, civics, mathematics, science, computer training, and mandatory language studies in English, Hindi, and Bhoti, alongside continued instruction in Buddhist teachings. Approximately 20 monasteries near the 3,000-km border with China have already committed to adopting the curriculum, with phased implementation planned for the remaining institutions.

Funding will be provided to monasteries to recruit qualified teachers and provide stipends, a significant shift as these institutions have historically relied on donations and foreign aid. The Central Tibetan Administration (CTA), which manages some monasteries, acknowledges its limited governance rights over the educational programs.

While officials emphasize the benefits for students – providing them with recognized qualifications and improved job prospects – the move is widely seen as a strategic response to China’s growing influence. A home ministry official, speaking on condition of anonymity, confirmed that streamlining education in these border regions is part of a broader plan to insulate religious institutions from external pressures.

This initiative feels like a necessary, if somewhat belated, step. For years, India has passively allowed a patchwork system to persist, potentially leaving a vulnerable space for external influence. Providing standardized, nationally-recognized education isn’t about suppressing Tibetan culture or Buddhist teachings; it’s about empowering students with the tools they need to succeed within India’s system and ensuring the long-term preservation of their unique heritage on their own terms. The emphasis on Indian history and civics, alongside continued religious instruction, strikes a reasonable balance.

However, the success of this program hinges on careful implementation. Ensuring adequate teacher training, providing sufficient resources to monasteries in remote areas, and respecting the autonomy of these institutions will be crucial. It’s a delicate balancing act, but one that could significantly strengthen India’s border regions and safeguard its cultural and strategic interests. The slow thaw in Sino-Indian relations doesn’t negate the need for proactive measures to secure these vital areas.